What does low academic self-esteem look like in the classroom? It looks like students who don’t ask questions because they are afraid of sounding dumb. It looks like students who give up easily or don’t try at all because they don’t want to fail.

More teachers are noticing low academic self-esteem in their students, especially in the post-pandemic classroom. Learning, by nature, comes with a risk of failure. Almost anyone who learns to ride a bike falls at some point. The difference is they get back up. Unfortunately, this fear of failure is preventing kids from engaging in the classroom at all.

It’s time to build a classroom of learners who have the self-confidence to try and fail. Teachers can foster curious students who ask questions and approach learning as a growth process. It isn’t easy, but it’s possible. Here is the path we need to take to help our students thrive in the future.

The Effects of the Pandemic Linger in School Hallways

For more than two years, COVID-19 has dominated discussions and dictated how people ran their lives. While this disease has become more endemic, the side effects of the pandemic continue to change how teachers and students approach education. Students (and their parents) are afraid that they are behind where they should be and will have a harder time succeeding in advanced classes, college and eventual careers.

“Nearly every child in the country is suffering to some degree from the psychological effects of the pandemic,” says Sharon Hoover, professor of psychiatry and codirector of the National Center for School Mental Health. “That’s why schools need to invest now in the mental health and well-being of our kids in a broad and comprehensive way—not just for children with learning disabilities and diagnosed mental health conditions, but for all students.”

Unfortunately, mental health resources alone can’t solve these high levels of anxiety and low academic self-esteem. A school counselor can assure a student that they are doing their best, only for a teacher to reinforce negative messages later in the classroom. Educators may need to rethink how they approach learning to help students build back their self-esteem.

“Without transforming student-learning supports, just adding more mental health staff in schools will contribute to the ongoing fragmentation and marginalization of efforts to cope with the increased number of learning, behavior, and emotional problems schools are confronting,” says Howard Adelman, psychology professor and codirector at the Center for Mental Health in Schools at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Students need to believe in their abilities. They need to know that they can learn, fail and try again in a supportive environment. This means rebuilding the classroom to create a space for students to thrive.

Stop Telling Kids That They Are Behind (And Parents, Too)

One of the first things to do when building up the academic self-esteem of your students, their parents, and even yourself is to leave political commentary about students falling at the door. It’s the job of your administration and district leaders to care about macro trends. Your focus is solely on the children in your classroom.

“It’s incredibly difficult to create a convincing argument out of the mountains of data that schools generate every year,” writes Jay Caspian Kang, staff writer for The New Yorker. “Politics too often becomes a frenzy over who can pick the right numbers out of a data set to justify what are ultimately political decisions.”

Every student has strengths and weaknesses. They understand some concepts while taking longer to grasp others. If each child in your classroom is both celebrated and challenged, they will focus more on their own goals and less on feeling behind.

“We cannot continue to operate from a deficit model where we believe they’ll achieve if the students just work harder,” says Nikki Glenn, a 5th-grade multi-classroom teacher and STEM Ed Innovators fellow. “If they aren’t succeeding, we need to reexamine ‘the work,’ not just the student. We have to start by finding ways to build up their confidence in themselves.”

Reframe Challenging Lessons and Expectations

Along with leaving discussions about education trends out of the classroom, it may be time to rethink how we approach learning and lessons. For example, instructional coach and reading specialist Peg Grafwallner, who wrote “Not Yet… And That’s OK: How Productive Struggle Fosters Student Learning,” encourages teachers to be transparent about concepts that students will likely struggle with.

“Tell your students that parts of the learning task will be challenging, but you have chosen this work because you know that with time and support, they’ll be successful,” she writes. “Explain to students that they’ll have access to you, their peers, and resources that will support them as they engage in productive struggle that demonstrates what they know and are able to do.”

Grafwallner says teachers tend to tell students that concepts are easy as a way to reduce their stress around learning them. Unfortunately, this can have the opposite effect. If a student fails to immediately grasp a concept they were told was easy, they might think they aren’t smart or have no chance of learning more difficult lessons.

By approaching lessons with the idea that everyone is going to learn at their own pace and have the support they need, teachers offer more of a growth mindset. This can help students overcome the idea that success in school isn’t something you have or don’t have.

“Society conditions many people to approach math with a fixed mindset, the idea that you are either good at it or bad at it and nothing you do can change that,” writes Sarah Fletcher at tutoring resource Applerouth. “However, mathematical ability is like any other skill. If you approach it with a growth mindset, you can improve!”

Small word changes can have a big impact on students. Even how you talk about your students when speaking with other teachers can frame how you see those kids and teach them.

“Our words build and foster our classroom communities,” writes Jillian Starr on her elementary education website. “How we talk to and about students (both in their presence and with colleagues and caregivers) can put up or knock down barriers to our students participating fully in our classroom communities. When we come from an asset model of thinking about our students, our words follow.”

Introduce the Idea of Successful Failure

So much anxiety about learning during the pandemic centered around testing and students failing to grasp important concepts. When parents and teachers put pressure on students to immediately grasp concepts and improve their test scores, kids inherently start to fear any type of failure. In order to build back their academic self-esteem, we need to help students realize that failure isn’t only okay — it’s a key part of learning.

“Children who attribute their grades to their own efforts and strengths are more successful than kids who believe they have no control over academic outcomes,” writes educational psychologist Michele Borba, author of “Thrivers: The Surprising Reasons Why Some Kids Struggle and Others Shine.”

“Real self-confidence is an outcome of doing well, facing obstacles, creating solutions and snapping back on your own,” Borba explains. “Fixing your kid’s problems or doing their tasks for them only makes them think: ‘They don’t believe I can.’”

Fear of failure can create learning paralysis. If a student tries, they risk failing. If they don’t try, there’s no risk of failure. These students are more likely to tune out in the classroom or give up on assignments easily. Teachers need to emphasize how failure is an essential part of growth.

“Experiencing failure helps kids gain valuable life experience,” says Kristin Carothers, a clinical child psychologist. “They learn to adapt to stress and push forward when things aren’t easy. Low-stakes activities — like board games or sports — are safe opportunities to learn that failure is a natural part of life.”

Rebecca Louick at Big Life Journal, a publisher and producer of mindset development tools, created a fun infographic demonstrating several ways to embrace failure. She encourages teachers to celebrate failure by letting students talk about mistakes they’ve made and what they learned from them.

For example, “Failure Fridays” can be the day you discuss a famous person who failed. Kids will relate to that, and may feel more comfortable talking about their own failures. You can also talk about the acronym FAIL, which stands for “first attempt at learning.”

Create a Safe Space to Ask Questions

A student who is afraid of failure or falling behind is less likely to speak up in class. They don’t want to say the wrong thing or miss an easy question with the wrong answer.

To improve your students’ academic self-esteem, give them opportunities to ask questions. These can come in a variety of formats so students who otherwise wouldn’t speak up can voice their concerns or confusion.

Holly Mitchell, a senior resource producer at K-6 teacher resource Teach Starter, gives several examples of how teachers can create safe spaces for students to ask questions. These include:

- Make questions anonymous by using sticky notes. Students can write questions and leave them on your desk or place them in a question board to review at the end of the lesson.

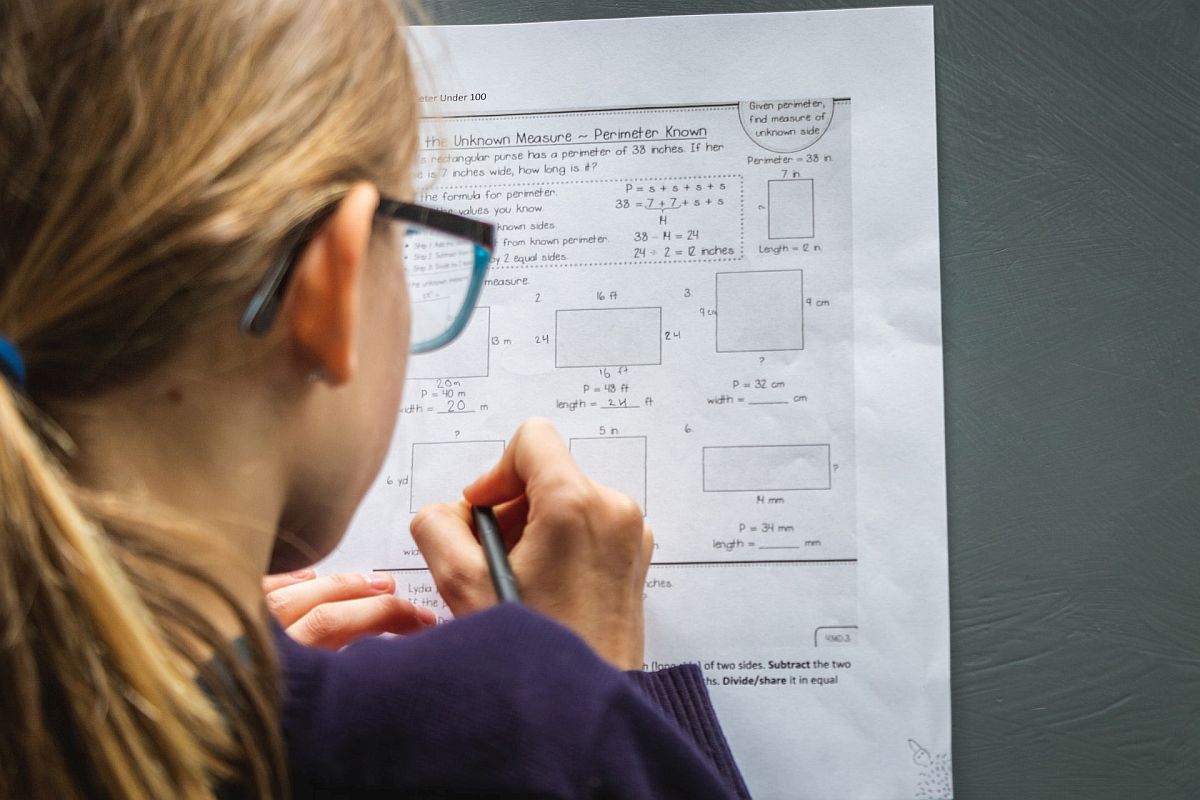

- Incorporate questions into every lesson plan. As a warm-up, display a photo and challenge students to ask questions about it. Who is in the picture? What are they doing? Why are they doing that?

- Let students signal for help. Develop ways for students to alert you to any struggles they are having without directing attention to them in class. One example is the use of different colored cups stacked on their desks. When a student needs help, they switch from a green to either yellow or red cup.

You might even change how you ask questions in the classroom to better open up student discussions.

Becton Loveless at Education Corner created a guide for asking and answering questions. How you pose a question can change how students answer. Managerial questions, for instance, can lead your students into the next part of the lesson: “Does everyone have a green pen?” Rhetorical questions, on the other hand, can remind students of something they know: “We need protein in our diet to help with growth and repair, right?”

Slight adjustments to how you lead classroom discussions and ask questions can open the door for more students to participate and build their academic self-esteem.

Focus on Falling in Love With Learning

This last part isn’t easy. As a teacher, you have piles of curriculum requirements you need to hit each year. You rarely have the luxury of letting students learn something just for the fun of it. However, if you can tap into the natural curiosity of children (and even teens) you may be able to better engage them.

First grade teacher Maura Renzi gives her students “voice and choice” by letting them discuss the material between themselves. For example, math lessons should focus on why and how students reach certain answers — rather than solely on the answers themselves. Similarly, reading lessons should focus on discussions and ideas, rather than reiterating plot lines.

“It builds confidence and self-esteem when they’re running the show and the teacher is just facilitating,” says Renzi.

This learning process also reinforces the material. Students don’t just learn the difference between area and perimeter, they can also explain why these concepts are important and discuss them with their peers.

There’s an idea in pedagogy that students can take back control of their education. They can see how a lesson ties back to a bigger part of the learning process. Even younger students can think about learning and how they approach challenging concepts.

“Metacognition refers to a student’s knowledge of their own thought process,” explains special education teacher and educational consultant Nina Parrish, who wrote “The Independent Learner.” “As early as kindergarten, teachers can instruct students in how to build their metacognitive skills through a process of planning, monitoring, and evaluating their learning.”

These processes can help you move away from instructing students to meet curriculum requirements to building up the knowledge base and foundational skills of learners.

Confident learners want to shout out answers even if they aren’t completely sure they are right. They want to ask questions and dive deeper into the course material. Not only will these learners retain more information, but they will make the classroom experience more enjoyable for other kids and their teachers. Try making a few changes to your classroom to see how your students’ academic self-esteem grows.

Images by: andreaobzerova/©123RF.com, jackf/©123RF.com, Greg Rosenke, CDC